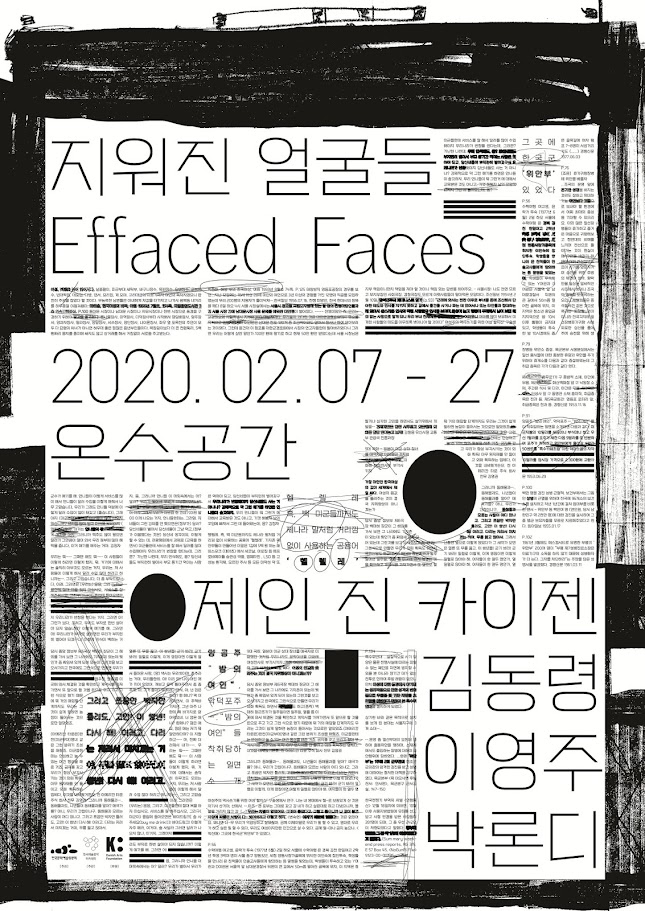

지워진 얼굴들

2020. 2. 7 – 2. 27

제인 진 카이젠 김동령 이영주 박론디

기획 | 이은수

주최 | 한국문화예술위원회

주관 | 한국예술창작아카데미

후원 | Danish Arts Foundation

장소 | 온수공간 1-3F

관람시간 | PM 12 - 7, 월요일 휴관

현세대의 한국 여성들은 지금 남성들과 전쟁을 치르고 있는것 처럼 보인다. 문화적으로는 전통적인 유교 사상이, 경제적으로는 90년대후반부터 지금까지 이어지고 있는 경제 성장의 둔화와 그로 인한 극심한 청년 실업이 종종 한국 사회에 만연한 성차별의 원인으로 지적된다. 하지만 반세기가 넘는 시간 동안의 전례 없는 경제 성장과 서구 문화의 유입 속에서도 차별이 지속적으로 계승되어 올 수 있었던것은 그것이 다른 정치적 이유로 인해 국가 권력에 의해 우리 사회에서 하나의 시스템으로 뿌리내리고 독려되어 왔기 때문이다.

한국은 빠르게 근대화되었지만, 분단과 휴전상태라는 근본적으로 불안정한 국가 정세는 지속되었다. 언제나 사상적, 물리적 전쟁 상태에 있다는 사실은 국가 권력으로 하여금 가부장제를 가속화하도록 했고, 사회 전반에 군대 문화가 스며들게 만들었다.

역사를 거슬러 올라가 보면, 해방 이후 여성들은 우리 사회에서 중요한 역할들을 수행해왔다. 일제 강점기(1910-1945) 와 한국전쟁(1950-1953) 사이 5년의 시간 동안 새로운 신념을 받아들인 여성들 사이에서 정치, 노동 조직의 형성이 활발하였으며, 이들은 국가의 정치적 경제적 건설에 적극적으로 관여했다. 남한에서 여성 조직은 전쟁의 발발과 함께 빠른 속도로 와해되었으나 전후 여성들은 전쟁이 남긴 폐허와 남성의 부재 속에서 생계를 부양하고 경제활동을 주도했다. 미군 주둔지에서 ‘양공주’라는 동경과 비하가 뒤섞인 별명으로 불리면서 미화를 벌어들였던 여성들은 60, 70년대 정부가 사회기반시설을 건설하고 기업을 육성하는 동안 국가 경제를 떠받쳐 왔다. 자본주의 사회에서 경제활동을 하는 개인은 그에 상응하는 사회적 발언권과 권력을 부여받게 되지만, 이는 전시 동원될 남성들의 사회적 입지가 약해진다는 것을 의미했다. 자연스럽게 여성의 경제활동은 천박한 것으로 틀지어졌고, 특히 그 경제활동이 양공주의 경우에서처럼 성적인 요소와 관련될 때에는 그 비하가 도덕적으로 올바른 것으로 용인되었다. 미디어에서 일어나는 반복적인 성차별적 이미지와 텍스트의 생산과 더불어 국가 권력이 여성들의 사회 활동을 억압하고 가부장적 사회 질서를 계승하도록 하는 공식적인 장치들 중 하나는 역사의 기록과 교육이다. 국민국가는 국가주의적 승리의 서사를 담아내는 사건들을 취사선택하여 계승하고, 나머지 기억들은, ‘기억의 구멍’에 겹겹이 묻어 버린다.1 본 전시는 국가 권력에 의하여 지워진 여성과 관련된 기억들을 불러내고, 국가적 희생양이나 성적인 이미지로 상징화 되어 축소, 반복 재현되는 과거의 여성들을 입체적 인간으로서 마주하여 사적인 대화를 나누려고 한다.

주디스 버틀러는 저서 ‘위태로운 삶’에서 역사적으로 특히 전쟁이나 분쟁에서 여성들의 얼굴은 말소되거나(effaced), 가치 판단이 부여된 개념의 상징으로 왜곡, 축소되어 반복 재현됨을 지적했다. 여성과 관련된 이미지들은 특정 맥락 속에 위치 지워지고, 사람들의 의식에 그것이 자리한 내러티브와 배경을 일거에 소환하여 고정되고 집단적인 감정을 일으키는 장치로 기능한다. 또한 이렇게 한번 구축된 재현시스템은 수용자들이 새로운 이미지나 텍스트를 접했을 때 그것을 기존의 내러티브 속으로 포섭시키거나 그렇지 못한 부분을 저항 또는 망각하게 하는 힘을 가진다. 따라서 대안적 내러티브를 어떻게 제시, 재현하는가는 어려운 과제이다. 대안적 재현의 개념으로서 버틀러가 분석하는 레비나스의 '얼굴 (face)’은 의도적으로 재현되지 않는 이들, 혹은 역으로 재현을 통해서 그 인간성이 제거된 이들의 얼굴뿐만 아니라 뒷모습, 목소리를 포함한다. 이 대안적 재현은 기존의 재현 시스템에서 지속적으로 탈주하려 하기 때문에 필연적으로 재현의 불가능성을 담지한다.

본 전시는 관람객들로 하여금 개인으로서 역사 속 여성들의 목소리를 나름의 방식으로 듣고 그 부름에 답하면서, “고통스러운 재구성이자 현재의 외상에 의미를 부여하기 위해 해체된 과거를 불러 모으는 행위” 로서의 역사쓰기에 동참하도록 독려한다.2 또한 그 기억, 상상,그리고 역사적 사실의 뒤섞임 속에서 객관적 사실을 선언하기보다는 주관적인 진실에 다가가려 한다.

제인 진 카이젠 ( J a n e J i n K a i s e n ) 은 신작 < P a r a l l a x Conjuncture > ( 2020) 에서 한국 전쟁 당시 세계민주여성동맹에서 파견한 조사단에 동행했던 덴마크의 사진작가 케이트 플레론( Kate Fleron ) 과 대화를 나눈다. 전국적 규모의 여성 정치조직이었던 조선민주여성동맹은 한국 전쟁 이전까지 남북한을 아우르며 활발한 활동을 벌였지만 전쟁의 발발과 함께 남한에서는 사회주의 사상을 배경으로 하고 있다는 이유로 국가권력에 의해 와해되었다. 그러나 북한에서 여전히 불씨가 살아 있던 이 단체는 세계민주여성동맹이 전쟁의 참상을 UN에 고발하기 위해 조사단을 파견하는 데에 중요한 역할을 했다. 북한을 방문한 조사단은 민간인, 특히 여성들의 피해를 이미지, 통계자료와 더불어 구술 증언의 형태로 자세히 담았다. 제인 진 카이젠은 한국전쟁의 결과를 살아가는 여성이자, 결과 그 자체로서 플레론이 남긴 당시 여성들의 사진과 이에 대한 텍스트를 마주한다.

오랜 시간 동안 기지촌 여성들을 담은 영화를 만들어온 김동령은 <밤손님들> (2020)에서 기지촌 여성 박인순과 혼혈인 안성자를 각각 창녀와 저승사자의 관계로 재회하도록 한다. 이 작품은 하나의 짧은 이야기, 일화와 같은 형식을 띠고 있지만 그 안에는 미군 부대 여성들이 서로 얽혀서 만들어낸 긴 역사가 담겨있다. 또한 이 환상적인 이야기는 박인순과 안성자가 지금도 안고 살아가는 기억과 고통을 가장 정직하게 마주하려는 노력이자 일종의 정화의식이다. 이와 함께 프로젝션으로 상영되는 내용은 주인공인 박인순의 삶의 한 조각을 담고 있다. 환상적인 이야기와 현실이 교차하는 가운데 관람객은 마치 편집실과 같은 환경에서 이를 관람하며, 상처를 가진 이들의 삶의 이야기를 어떻게 재현할 수 있을 것인가라는 고민에 동참하게 된다.

이영주 작가의 <검은 눈> (2019) 은 미군이 10년이 넘는 기간동안 태평양에서 감행한 수소폭탄 실험에 대한 자료 영상으로 시작해, 그것이 만들어낸 변종의 생물들이 살아가는 디스토피아를 상상한 애니메이션으로 이어진다. 작가 자신의 얼굴을 한 기형의 소녀 혹은 여성들은 역사적, 체제적, 그리고 물리적 폭력의 잔해 속에서 살아간다. <For Whom Do They Sing>(2020) 은 남한 걸그룹의 뮤직비디오 위에 북한 여성들의 체제 찬양적 공연 모습을 겹쳐 놓았다. 자본주의와 공산주의라는 두 체제가 가지는 거대한 불화에도 불구하고,여성들은 그 속에서 일관되게 반짝이는 장식적 요소로 축소되고 도구화 된다.

박론디 작가의 <안녕, 거기 누구 있나요?> (2020) 는, 관람객이 기지촌 여성들의 삶을 아주 사적인 공간에서 만나도록 한다. 천막 주위에 장식된 도상들은 기지촌 여성들의 삶과 그들이 사회와 맺어온 관계를 시각화한다. 천막 안으로 들어서면, 관람객은 점괘를 뽑는 것처럼 자신이 마주하게 될 하나의 이야기를 선택하게 되고, 거기서 기지촌 여성들의 발화, 혹은 그들과 관련된 사회적 발화들을 만나게 된다. 박론디 작가는 관람객이 그들의 삶을 공식적 기록이 아닌 개인의역사로서 마주하도록 하며, 기지촌 여성들의 삶과 그들 위에 건설된 지금 우리 사회, 그리고 관람객 자신이 영위하는 현재의 일상이 어떤 밀접한 관계로 엮여있는지에 대해 인식하게 한다.

박론디 작가의 <안녕, 거기 누구 있나요?> (2020) 는, 관람객이 기지촌 여성들의 삶을 아주 사적인 공간에서 만나도록 한다. 천막 주위에 장식된 도상들은 기지촌 여성들의 삶과 그들이 사회와 맺어온 관계를 시각화한다. 천막 안으로 들어서면, 관람객은 점괘를 뽑는 것처럼 자신이 마주하게 될 하나의 이야기를 선택하게 되고, 거기서 기지촌 여성들의 발화, 혹은 그들과 관련된 사회적 발화들을 만나게 된다. 박론디 작가는 관람객이 그들의 삶을 공식적 기록이 아닌 개인의역사로서 마주하도록 하며, 기지촌 여성들의 삶과 그들 위에 건설된 지금 우리 사회, 그리고 관람객 자신이 영위하는 현재의 일상이 어떤 밀접한 관계로 엮여있는지에 대해 인식하게 한다.

작품들과 유기적 관계를 이루는 아카이브는, 여성의 역사와 관련된 사진들과 사료, 구술사 기록을 발췌해서 보여준다. 천위에 인쇄된 자료들은 나무 구조물의 여러 면에 중첩되거나 주름져서 전시된다. 관람객들은 구조물 주위를 돌아가면서 천을 펼쳐보고 들춰보는 가운데 직접 그 구성에 관여하면서 저마다의 이야기를 상상해 볼 수있을 것이다.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 발터 벤야민, 역사의 개념에 대하여, 최성만 역, (서울: 도서출판 길, 2008) 참조

2 호미 바바, 문화의 위치, 나병철 역, (서울: 소명출판, 2012), 152 p

글 이은수

➕

➕

Art bava.com

Art bava.com

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It seems like Korean women of this generation are at war with men. The long tradition of Confucianism and widespread youth unemployment due to the economic recession that continued from the late 90s are often identified as the reasons behind it. However, gender discrimination has been able to survive, if not worsen, in Korean society despite unprecedented economic growth and the rapid influx of Western culture throughout the second half of 20th century. It remains because sexism was deeply entrenched in the social system and officially encouraged by the state for certain political reasons.

While becoming dramatically more modernized, Korea has experienced fundamental political unrest, specifically as it was divided into the North and the South in 1953 and because it has since been in a state of armistice. The country's consistent engagement in ideological and physical disputes caused the state to promote patriarchism, which resulted in the prevalence of military culture.

Since the country’s liberation, Korean women have played many important social roles. During the five years between the end of the Japanese Occupation (1910–1945) and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–1953), there was a great increase of feminist organizations and women’s labor unions that were actively engaged in the restoration of political and economic structures of the country. Although the feminist movement had rapidly collapsed with the outbreak of the Korean War, it was women who led the economic activities and provided for their families amid the ruins of the war. In the 60s and 70s, when the country was trying to foster businesses and build infrastructures, the camptown ladies, nicknamed ‘Yang-gongjoo,’ a derogatory term meaning Yankee princess, supported the state economy with the dollars they earned.

Capitalism, by nature, lends a person with certain economic power a similar amount of social influence. For the state, however, this meant that the social status of men, their potential mi litary force, was at risk. Hence the economic activities of women were framed as something vulgar, and the public shaming of women became socially acceptable, or even praiseworthy, especially when the woman was involved in the sex industry.

Along with the continuous reproduction of gendered images and texts by the media, one of the official mechanisms that the state often deploys to oppress women’s social engagement and propagate the patriarchal social order is through the documentation and teaching of history. A nation-state chooses to educate its population about the historical events that can contribute to the narrative of nationalistic triumph, while burying the rest of the memories. Effaced Faces tries to call upon the memories of women effaced by the state and to recognize those women, not as images reduced to mere victims or sexual objects, but as human beings, and engage in private conversation with them.

Judith Butler, in her article ‘Precarious Life,’ pointed out that in history, especially when related to conflicts, the faces of women are effaced or reduced to symbols of concepts endowed with value judgements. Images of women, fixed into specific contexts, invoke collective emotions when viewers recall the historical narratives and backgrounds in which they are placed. Once constructed, the system of representation forces viewers to understand the images and texts through its lens and to be oblivious to the images and texts that cannot be assimilated to it. Hence, building and representing alternative historical narratives becomes a difficult task. Butler analyzes the Levinasian concept of ‘face’ as an alternative means of representation. This ‘face’ includes not only the faces but also the backs and voices of those dehumanized by the representation or whose representation is intentionally effaced.

This alternative method of representation inevitably holds the impossibility of the representation in it, as it constantly tries to escape from the existing representational system.

This alternative method of representation inevitably holds the impossibility of the representation in it, as it constantly tries to escape from the existing representational system.

This exhibition encourages viewers to listen to the voices of women from the past and respond to them, while also participating in “collecting the debris of past and re-membering them” which is also a “painful process to understand present trauma.” And in this mixture of memories, fictions, and historical documents, this exhibition tries to get closer to the subjective truth, rather than defining objective facts of history.

Jane Jin Kaisen will present a new work, Parallax Conjuncture (2020), in which she converses with Danish photographer, Kate Fleron, who accompanied the delegation of Women’s International Democratic Federation ( WIDF) during the Korean War. The Chosun Democratic Women’s Federation was a nationwide women’s organization active both in the North and the South. However, it was disbanded by the military regime in South Korea shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War because it was based on socialist ideologies. In the North, the WIDF remained active and played an important role by dispatching a delegation to report the horrors of the Korean War to the United Nations. The delegation published images, statistics, and oral statements of women in Korea. Kaisen includes images and texts that Fleron left after her journey to Korea that capture the experiences of a Danish woman living in the aftermath of the Korean War and the consequences of the Korean War itself.

Throughout her career as a film director, Kim Dong-ryung has focused her work on the lives and dreams of camptown ladies. In her short film, The Night Guests (2020), camptown lady Park In-soon and Ahn Seong-ja, a daughter of a camptown lady and a black American soldier, are reunited as a prostitute and a messenger of death, respectively. The work takes on an anecdotal character as it interweaves the long histories of the camptown ladies. This fantastical story is an exorcism, and an effort to face their painful memories in the most honest way. The projection accompanying the short film contains some moments of the life of Park In-soon. The viewers, going back and forth between the reality and the fantasy in the space that has the atmosphere of an editing room, are invited to contemplate how the life stories of the ones with traumatic experience can be represented.

Black Snow (2019) by Lee Young-joo begins with archival footage of hydrogen bomb tests done by the United States over the course of more than ten years in the middle of Pacific Ocean. It then shows an animated film that features an imagined dystopia with nuclear-spawned mutant species. In it, deformed girls and women with the face of the artist herself survive the aftermath of historical, physical, and systemic violence. In For Whom Do They Sing (2020), footage of a North Korean girl band's gig that praises their leader and the ruling party overlaps with a music video of a South Korean girl group. Despite the ideological discord between capitalism and communism, the girls are marginalized and instrumentalized as decorative elements in both social systems.

With her work Hello, is anyone there? (2020), Rondi Park forces the audience to encounter camptown ladies in a private place: a small tent embroidered with decorative icons and created in the exhibition space. The icons represent the lives of camptown

ladies and their relationships with Korean society. When visitors enter the tent, they can draw a little stick from a cylindrical case to select a story they will learn through oral statements of camptown ladies and social statements related to their lives. By encountering these camptown ladies through their personal stories, visitors are able to recognize how their everyday lives are closely connected with the lives of camptown ladies and the society that was built upon them.

ladies and their relationships with Korean society. When visitors enter the tent, they can draw a little stick from a cylindrical case to select a story they will learn through oral statements of camptown ladies and social statements related to their lives. By encountering these camptown ladies through their personal stories, visitors are able to recognize how their everyday lives are closely connected with the lives of camptown ladies and the society that was built upon them.

Archives with historical images, documents, and oral statements are presented along with the artworks. These materials, which are printed on fabric, are exhibited wrinkled and overlapped with one another. Viewers are encouraged to construct their own version of stories while unfolding and lifting the fabrics.

Curation & Text - Eunsoo Yi

1 See Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History (California: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016)

2 Homi K.Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 62

Curation & Text - Eunsoo Yi

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2 Homi K.Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 62